Bootstrapping's Missing Warning Labels

It's been over a year running my AI flashcard startup Janus and the reality of solo bootstrapping is a lot harder than I thought. The instruction manuals from successful founders were missing a couple warning labels. Fundamentally, some of the principles that startup operators have been following break-down at the microscopic scale of a one-person company.

I don't want to dissuade you from starting (spoiler: I'm still going at it). I want to help pre-empt any "if only I had known" moments.

Personal Profitability != Business Profitability

The defining quality of a bootstrapped strategy is that you aim to be immediately profitable; this is in contrast to a funded strategy where you defer profitability in favor of growth. This dichotomy presents bootstrapping as sustainable, organic and even potentially less risky route because the unit economics of the business don't have a question mark around them.

Don't forget to include your living expenses in that equation. Your business can be making a profit, but if it's less than the cost of rent and food, you will lose money. Earning enough to plug the burn rate is called "Reaching Ramen Profitability". You know you're there when you don't have to worry about buying microwave ramen, sleeping on a futon, and renting a studio apartment.

That may sound very obvious but it probably will take you about 2 years to get there and chances of going the distance are sub 10%. The part about bootstrapping being immediately profitable is very misleading: It's just as "guaranteed" and "immediate" as getting a US visa.

You have a couple options other than having to endure the pain of burning your savings:

- Get a part-time job, or work on this as as a side-hustle to your existing full-time job: This increases your income floor and de-risks the operation. But you decrease momentum and might miss the timing to catch the wave.

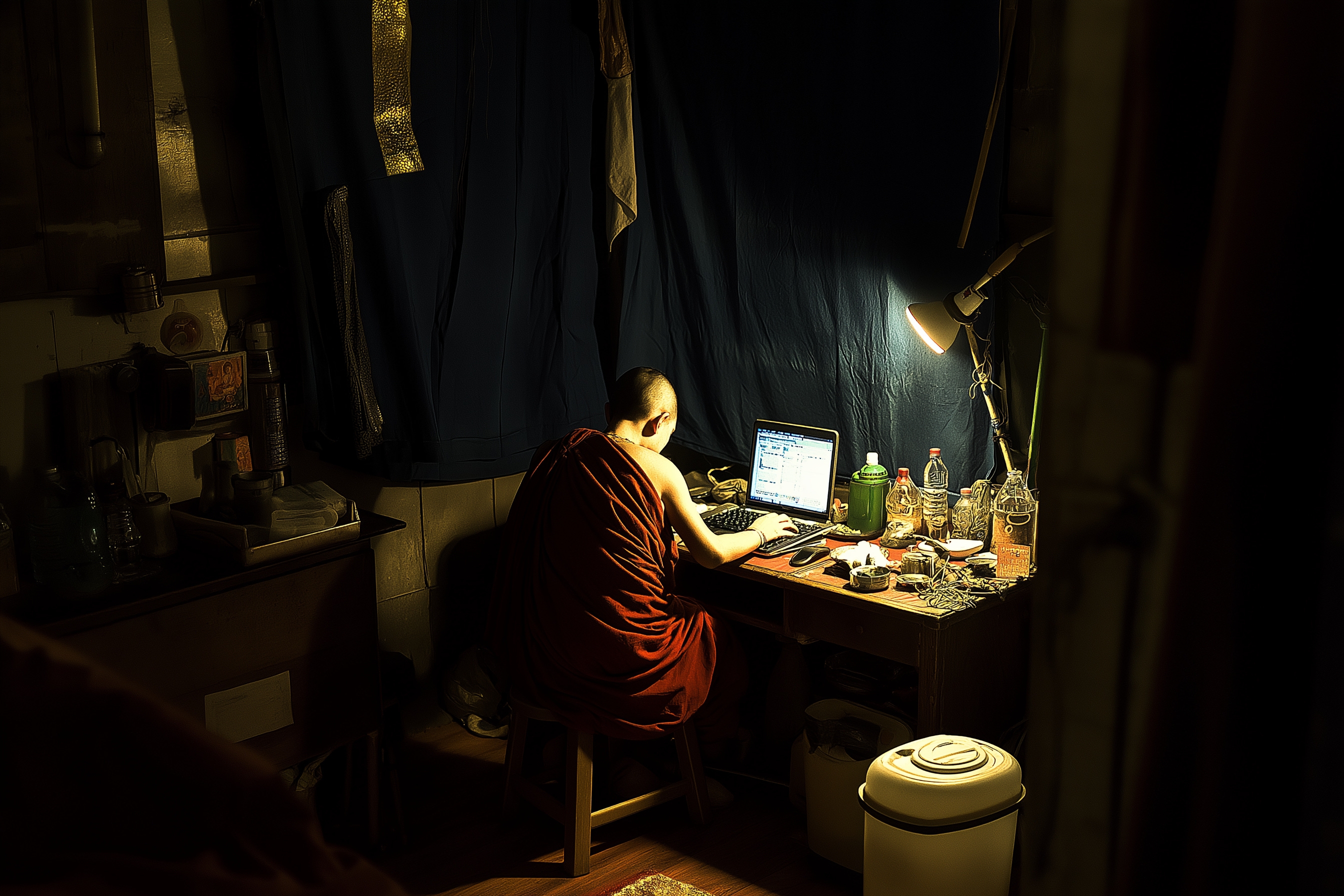

- Move back in with parents: Considering many Gen-Z never moved out, there is probably far less cultural shame then before. If they are supporting and have the means, your parent's house can become the monastery for you to go into monk-mode. It worked for David Park and Jack Friks

I'm not quite at that stage yet but it's honestly something I've considered.

Your Audience is Quiet

The empirical entrepreneur says "find out what your user wants from data". "Listen to what they want". But what if you can't properly hear them because the audio is too quiet and noise starts to dominate?

Janus has had over 1k users sign up, with about 80% actually making flashcards. From that crowd, I've had calls with maybe 15 users and chatted on Discord & Reddit with a further 35 . My audience is mainly university medical students and they are too busy studying and partying to get on a 15-30 mins call with a stranger.

In these infrequent calls, I ask about how they study & their existing workflows, any issues they've had so far, and what essential features they would want. It turns out students have very diverse and idiosyncratic ways of digesting lecture material. And that means they have a very different set of needs that often don't overlap. It's difficult to prioritize features when the candidate tasks have only 2-3 votes.

The Lean Methodology also breaks down at small samples. A/B testing metrics in PostHog for weekly cohorts of 20-30 is like reading tea leaves in your first divination class at Hogwarts. The numbers are so sensitive to variance that someone using multiple Gmail accounts to get through more trial credits can give the illusion of an uptick.

How I could have made them louder

With that said, I have made the poor decision not to consistently share the project, even after release. I first shared Janus to the world in end of March 2025. It was really unpolished and has since undergone 2 major workflow iterations across 6 months. I took the advice of shipping early, but across the year, I did not market it any further: no reddit posts, no short-form social media, no influencers, no personal blogs, nada. My mistake was forgetting that software is never in a finished state. And it's obviously very naive to think people will just magically find out about your product via word of mouth. If I was posting regularly, I would have gotten more traffic, more sales, and more intel into what to build next. I fell into the trap of spending my time on what I enjoyed and am good at, instead of what I needed to. I missed out developing marketing skills 6 months ago and now have to cram.

Productivity Debuffs

There are definitely advantages to working solo: no pointless meetings, no organization overhead, no onboarding, no conflict over decisions.

But there are some very meaningful debuffs.

Less Cumulative Horse Power

- Smaller Budget: If you are against a team of 4 working on a similar idea for 1 year, they have 3 years of extra budget over you. That's huge when you consider that your proclaimed "killer feature" could realistically take you only 2-3 months with AI code gen.

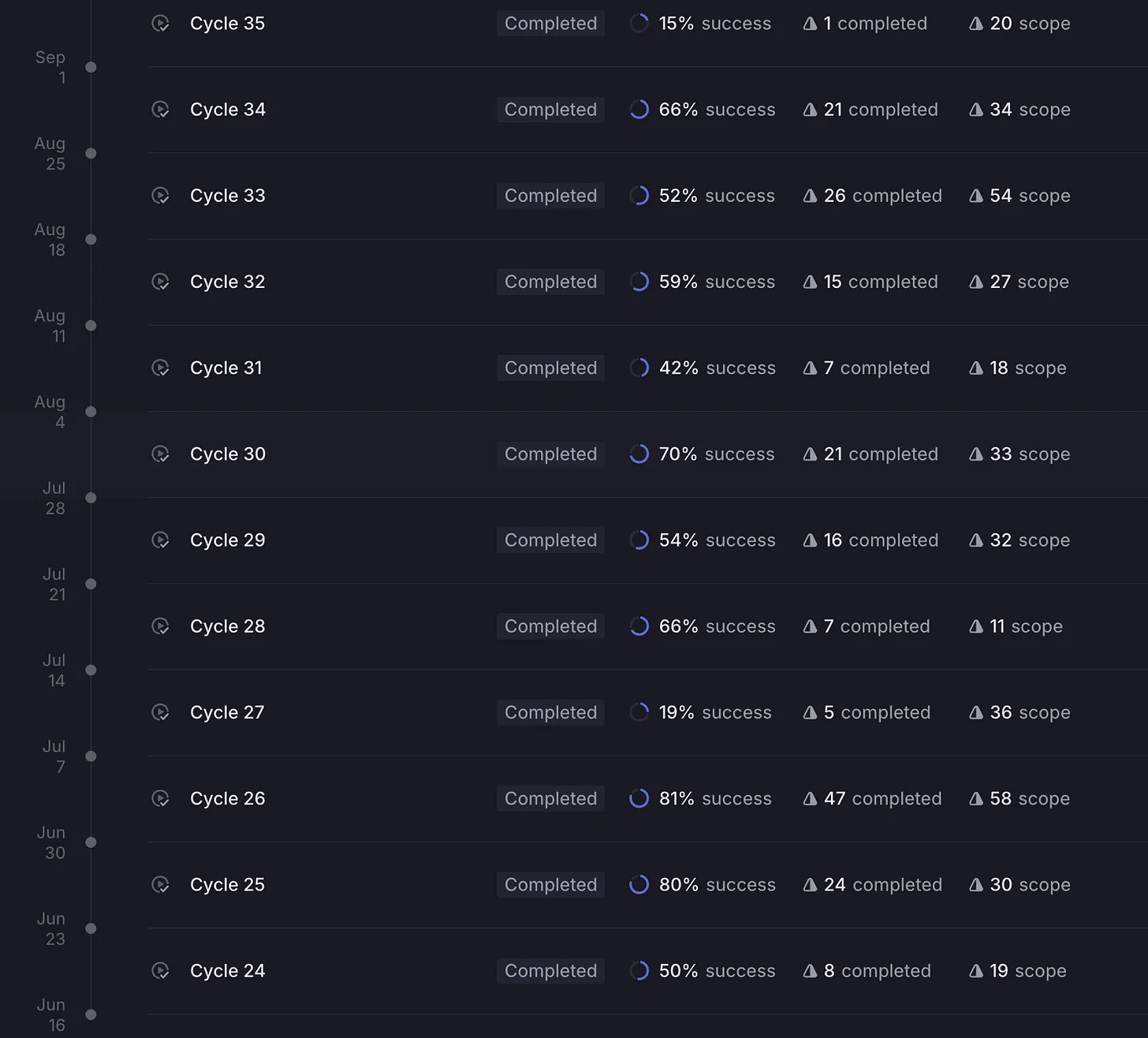

- Progress only happens when you do work: It's a myth that we sustain productivity non-stop. Take a look at how sporadic my linear weekly cycles are. During the weeks where I get 47 units of work done, I feel great. The weeks where I get sub 10, I stare at my product, notice no difference to last week and think, "what have I been doing all this time?". It's the double whammy of low productivity and subsequent low moral that sucks. But when you are working in a team, oscillations in individual productivity will cancel out and lead to consistency output.

- No one to bounce ideas back and forth with: Creative pool of ideas is limited, and the obvious and highest return ideas may get missed.

Meta Work Tax

- Context switching: The solopreneur is the ultimate generalist: dev, marketer, business strategy, sales, accountant. But it's a massive mistake to try flip-flopping between these tasks in the same hour of work. It might seem appealing to make branding material while your Cursor coding agent hums away at a ticket but you are unconsciously juggling more in working memory and this cognitive strain will burn you out much quicker. Whenever I am undisciplined and forget to focus on doing just one thing, I start to go cross-eyed in the evenings.

- Forever a Dilettante: Getting better at your craft boosts productivity. You need to spend time on things other than producing the final output. Consume quality content and develop a capable palate (I fail to do this consistently and it's one of my biggest regrets). Google historically had a policy that granted you 20% of the working day to explore side projects. As the only employee, burning a tight runway makes it harder to justify investments in long-term learning

- No Overhead Amortization: You need to prioritize work. That means sitting down, going through Linear tickets + user feedback and deciding what to work on next. I sometimes spend about 2 hours on a Monday scheduling work. That's both a meaningful chunk of attention and time, and also likely an underestimate. For teams though, the marching orders need to be drawn up once and then the team can be set in motion. In theory, the larger the team, the smaller the overhead of project management.

Know what you're signing up for. The playbooks will tell you it's a marathon. They won't mention you're running it alone, in the fog and dark. I hope this post at least equips you with a head lamp.